The Flour Mill

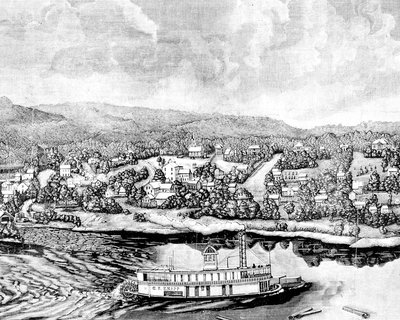

It’s long gone, but in front of you across Highway 95 was one of Minnesota’s earliest flour mills. The flour mill was an important economic engine for the maturing Marine Mills that outlasted the town’s founding sawmill and lumber business by 40 years. After establishing a sawmill in 1839, the lumber company partnered with Dr. James Gaskill to construct and operate a flour mill in 1855, reportedly giving the town its plural name. Agriculture and grain milling flourished and allowed Marine Mills to become economically independent of the lumber industry, which ended in the 1890s.

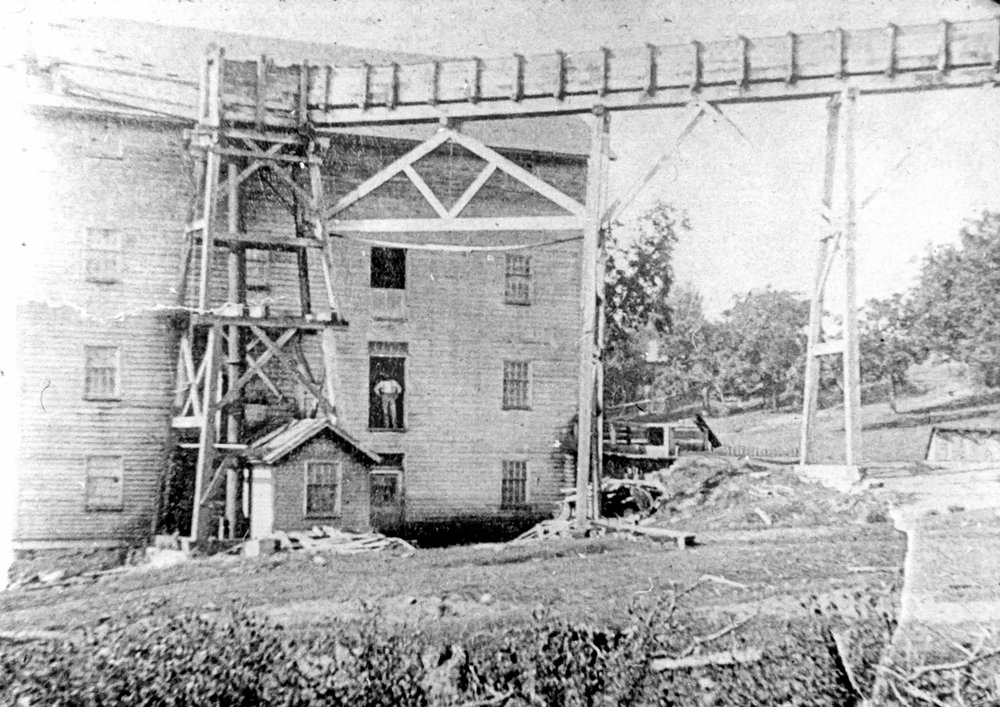

The flour mill was located along the Mill Stream west of the sawmill. The flour mill, like the sawmill, was run by waterpower. Although the flour mill was located on the lower Mill Stream, it got its power from a higher-elevation mill pond created by damming the Mill Stream above the falls at Broadway St. Water from this pond was conveyed on an elevated wooden mill race to the mill where it dropped four-stories onto a waterwheel that turned the millstone.

The mill ground corn, wheat, barley, and oats into the best flour and grist with a millstone imported from France. One of the original millstones is by this historic marker and another is on display at the Stone House Museum.

Freshwater quartz quarried in northern France produced the whitest flour and provided stones that held their edge far longer than inferior products. The French stone is only found in small blocks so a millstone had to be carefully pieced together, cemented, and bound with iron bands to endure constant use.

In 1880, the mill was taken over by John G. Rose, who also was part-owner of two general stores in town. Rose built a large house by the mill for his family. His daughter Laura Rose recalled:

I remember the prosperous days when the farmers’ wagons were sometimes lined up almost down to the main street waiting to unload their grain. Sometimes some of them had to stay overnight. There was a long shed and even a little house across the creek with a stove, chair and a bed where they could spend the night. Remember, those were horse and buggy days, and they came from up to sixteen miles to get their wheat ground into flour. [Sonbuchner, 2003, p. 83]

After John Rose died in 1898, the mill was renovated and operated by M. Joseph Gable from 1900 until 1930, when the mill went idle due to competition. According to Laura Rose:

You might say the Minneapolis flourmills brought our flour mill hard times. At least it was the main cause. These mills were expanding very quickly. Grain elevators were being built nearer to our farmers, and they found it much more convenient to haul their grain there for cash and buy flour there. Besides, Minneapolis flour was whiter and less heavy than ours. They could afford the newest and best machinery to be had – our little flourmill could not. The result was fewer and fewer grain wagons came to our mill … With the loss of the prosperous mills, the town as a whole came into hard times until it became adjusted to being just a pleasant village where it was very nice to make our homes. [Sonbuchner, 2003, p. 83]

Joseph Schorr bought the mill in 1935, removed the top three stories and kept the bottom two for his Schorr Ice Cream Company. Customers claimed Schorr “makes the best ice cream in the world.”

In the end, the diminished remnants of the flour mill became a factory for Norcroft Division of Northwest Plastics. Everything was finally destroyed by a factory fire in 1956.

— Andrew Kramer and the Marine Historic Signage Committee